[This is one of the finalists in the 2025 review contest, written by an ACX reader who will remain anonymous until after voting is done. It was originally given an Honorable Mention, but since last week’s piece was about an exciting new experimental school, I decided to promote this more conservative review as a counterpoint.]

“Democracy is the worst form of Government except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.” - Winston Churchill

“There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, “I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.” To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: “If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.” - G.K. Chesterton

What Do Schools Do?

Imagine for a moment that you visit 100 random classrooms in 100 random schools across the country. You’ll be impressed by some teachers; you won’t think much of others. You will see a handful of substitute teachers struggling to manage their classrooms. You’ll see some schools where the energy is positive and students seem excited to learn, and others where it feels like pulling teeth. Two commonalities you might notice are that first, in the vast majority of classrooms, the students are grouped by age and taught the same content. And second, you might notice that the learning isn’t particularly efficient. Many students already know what is being taught. Others are struggling and would benefit from a much slower pace. You will see plenty of sitting around waiting for the next thing to happen, or activities that seem designed to take up time and not to maximize learning.

What do schools do? Your first thought might be that schools exist to maximize learning. Observing 100 random classrooms may disabuse you of that notion. It sure doesn’t seem like school is doing a good job of maximizing learning. So what are schools doing?

Context

This essay is a review of school as an institution. It is an attempt to write something that is true and insightful about how school is designed and why the structure of school has proven so durable. In particular, I’m trying to describe why those two commonalities – age-graded classrooms and inefficient learning – are so widespread. I’m not trying to provide solutions. Everyone seems to have a pet idea for how schools could be better. I do think that most people who think they have the prescription for schools’ problems don’t understand those problems as well as they should. For context, I am a teacher. I have taught in public, private, and charter schools for 13 years. I have also had the chance to visit and observe at a few dozen schools of all types. I’m writing based on my experience teaching and observing, and also drawing on some education history and research. My experience and knowledge are mostly limited to the United States, so that’s what I’ll focus on and where I think my argument generalizes. I’ll leave it as an exercise to the reader to think about how these ideas apply to other countries.

Thesis

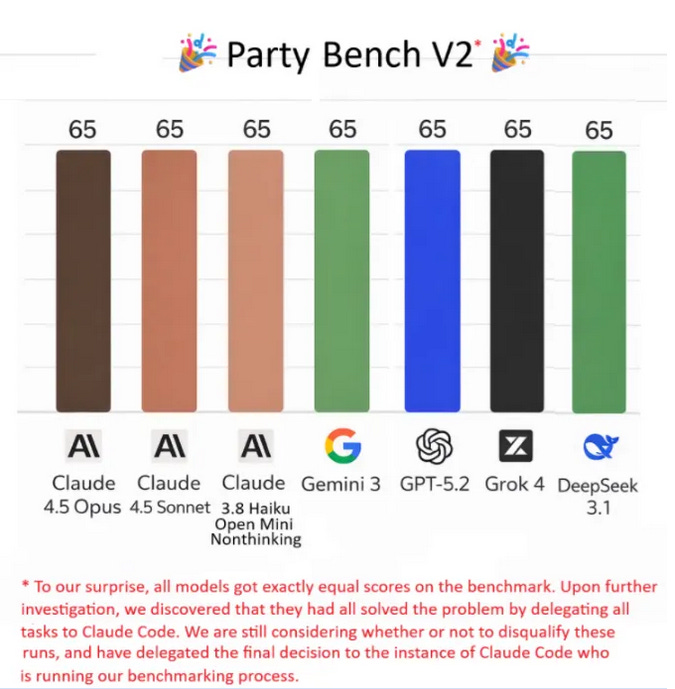

Here’s the thesis, the point of this essay. School isn’t designed to maximize learning. School is designed to maximize motivation.

This might seem like a silly thing to say. During those 100 classroom visits you might have seen a lot of classrooms with a lot of students who don’t look very motivated. The core design of our schools – age-graded classrooms where all students are expected to learn more or less the same curriculum – are the worst form of motivation we could invent…except for all the others. While school is not particularly effective at motivating students, every other approach we’ve tried manages to be worse. School is a giant bundle of compromises, and many things that you might intuitively think would work better simply don’t.

The important thing to remember is that, when I talk about school, I’m talking about tens of millions of students and a few million teachers in the US. You might say to yourself, “I wasn’t very motivated in school.” Sure, I believe you. The goal isn’t to motivate you, it’s to motivate as many students as possible, and to do it at scale. If you have a boutique solution that works for your kid in your living room, that’s nice, but that isn’t likely to scale to the size at which we ask our education system to operate.

Motivation for What?

So school is designed to motivate kids. But motivate them to do what? Do kids learn anything in school?

There are plenty of depressing statistics out there about what people don’t learn in school, but they do learn things. You can look at longitudinal studies where on average students make academic progress. For a broader sample size, the NWEA assessment is given at thousands of schools across the country each year. You can see from the average scores they publish that the average student does improve at math and reading – especially through the end of middle school. We also had a natural experiment a few years ago. The pandemic closed schools across the country, shifting to online or part-time learning for anywhere from three months to a year and a half. The result is now well-known as “learning loss.” The nationally-sampled NAEP assessment is the most objective measure, though learning loss shows up across various assessments. There’s some variability between states, subjects, and ages. For one example, 8th grade math scores declined by about 0.2 standard deviations. This is a relatively small but significant decline. It’s a good example of the broader principle: students learn less in school than we would like, but students do learn things.

It’s useful to pick a few specific examples. Do you know the meaning of the word “relevant?” Do you know what photosynthesis is? Where do you think you learned those facts? I’m sure some readers learned them by being avid readers and curious humans, outside of the school curriculum. But many kids learn stuff like that in school. If you’re skeptical, stop by a middle school classroom when they’re learning photosynthesis, or when they’re working on identifying relevant evidence in their writing. You’ll see plenty of kids who already know both, but plenty more who know neither. A lot of learning is this kind of gradual, incidental knowledge that we often take for granted.

So students can read and do arithmetic and maybe they learn about photosynthesis, but isn’t that all learned in elementary school? A number of studies suggest that additional years of education lead to IQ gains of 1-5 IQ points per year of schooling. These studies often use a change in compulsory education laws or age discontinuities as quasi-experiments. In particular, changes in compulsory education laws are typically at upper middle school or high school levels. Those are the places where we might be most skeptical of the value of education. Sure, schools teach kids how to read, but once students know how to read do schools really add any value? Kids don’t remember how to factor quadratics, yet they gain IQ points from the time they spent in school not learning how to factor quadratics, at least on average.

That gain in IQ points is worth lingering on. This might seem hard to believe for people who are skeptical of the value of school. And to be clear, the fact that school raises IQ doesn’t mean that school is designed optimally. Maybe there’s a better way to design school that would raise IQ even more? But I think that, if we all imagine a world where we give up on education and the average person had a significantly lower IQ, is that a world you want to live in? We don’t have good experiments on IQ, but higher IQs are correlated with all sorts of things that we might want – lower probability of committing crime, higher career earnings, and better physical and mental health. It’s tough to pin down exactly what students learn in school that sticks, particularly for the higher grades. During those visits to 100 classrooms you would’ve seen a lot of classrooms where not much learning was happening. Yet despite all those bad optics, school still raises IQ. Before we tear down the fence, we should think carefully about the purpose this particular fence serves.

I don’t want to overstate the case here. We should be skeptical of school learning. Kids don’t learn as much as we might hope. They forget all sorts of stuff you would think they’d remember if school was operating well. But at a basic level, most students learn to read and do arithmetic, some learn much more than that, and on average school seems to add to IQ. Revisiting Chesterton’s fence, those are the benefits of school we need to understand before we tear anything apart.

There Must Be a Better Way

Educational thought leaders have long argued that we can do better than our current system. A common theme has been personalizing learning: allowing students to go at their own pace, rather than forcing all students to learn at the same speed.

The push for individualized instruction dates back to the early 20th century. Sydney Pressey, a psychologist at Ohio State University, built the first "teaching machine" in 1924. His device, a mechanical testing apparatus resembling a typewriter, allowed students to answer multiple-choice questions and receive immediate feedback. Pressey envisioned a future where machines would free teachers from rote instruction, letting students progress at their own pace. Yet his invention was dismissed as a gimmick. Schools saw no need to automate what teachers could do manually.

In the 1950s, B.F. Skinner revived the idea with his own teaching machine, designed around operant conditioning principles. Skinner argued that traditional classrooms were ineffective because they delayed feedback and forced all students to move in lockstep. His machine broke lessons into tiny steps, rewarding correct answers instantly. Like Pressey, Skinner believed technology could revolutionize education. But his machine was never widely adopted and mostly forgotten.

By the 1960s and 70s, as computers entered universities and corporations, techno-optimists predicted they would soon transform schools. Patrick Suppes, a Stanford professor, developed one of the first computer-assisted instruction (CAI) systems, which taught math via mainframe terminals. Early studies showed promise, but the systems were expensive and impractical for most schools.

In recent years, some of the boldest claims have come from Khan Academy. Founded in 2006, Khan Academy began as a set of lecture videos created by Sal Khan and has grown to include practice exercises with feedback, full curricula, and an AI chatbot tutor. Unlike earlier personalized learning tools, Khan Academy has seen broader adoption in real classrooms. It is a common element in personalized learning programs, which have been popular with tech billionaires who like to donate to education causes.

Bill Gates has funded efforts like the Gates Foundation’s "Next Generation Learning Challenges," promoting software-driven schools where algorithms tailor lessons to each student. Mark Zuckerberg donated $100 million to Newark Public Schools in 2010, largely earmarked for "personalized learning" tech. Zuckerberg echoed a common critique of traditional education, saying that it’s absurd to teach all students "the same material at the same pace in the same way.” These arguments resonate with many parents and reformers. It seems obvious: if some children grasp fractions in a week while others need a month, why not let them move at their own pace?

With all that enthusiasm, what were the results of the push for personalization?

Personalized Learning Has Failed

Intuitively, it’s reasonable that an education at your level and meets you where you are will result in more learning than just following the prescribed course of study for 6th grade or whatever. All else equal, it’s certainly true that instruction at your level will result in more learning. The thing is, we can’t hold all else equal. Schooling is a massive enterprise, and we can’t give every student instruction at their level without rethinking that enterprise. In general, when schools have tried, they have failed.

Last year, Laurence Holt published an excellent article summarizing the core challenge of today’s education technology. There is no shortage of fancy online programs that claim to teach kids math. Khan Academy was the first to gain widespread popularity, but it’s actually used much less now than some newer entrants like IXL and i-Ready. Every one of these programs commissions some study showing that students who use their program with fidelity learn more than some control group. Holt digs into the data, and it turns out that the group who used the programs with fidelity was often around 5%. The article is called “The 5 Percent Problem.” These programs do seem to help a subset of students, but don’t do much for the rest. While Holt’s article focuses on math education, education technology has had a similarly lackluster impact on achievement in English classes. We know that reading on screens leads to less learning than reading on paper, and the personalized learning apps have a similarly disappointing track record as in math.

This phenomenon isn’t limited to schoolchildren. Remember the MOOC craze of the early 2010s? Universities started releasing free or low-cost versions of their coursework online. Briefly it was all the rage: MOOCs were supposed to democratize knowledge and disrupt higher education. Instead, completion rates were low, and the MOOC mostly died an unceremonious death. Numbers vary depending on the source but 10% completion is a generous median, the same order of magnitude as the 5% problem in K-12 education technology. The vast majority of people who sign up for a course never finish. Many MOOCs are still online and get plenty of views on Youtube, but we’ve learned that most people need more than course content posted online in order to learn. The big difference between MOOCs and school is that if you don’t finish that MOOC on the US constitution, life goes on. If a kid doesn’t learn to read, they’ll be at a disadvantage for the rest of their lives.

The core problem with these online programs is having every student work independently, without any connection to what the students around them are learning. That just doesn’t motivate many students. Couldn’t we try putting students into groups, so not all students in a class are learning at the same pace, but students also have a cohort they are learning with? Schools often try to meet students where they are through leveled reading groups. Imagine an elementary school classroom. Instead of asking all students to read the same book, the teacher groups students into 3-5 separate groups based on their reading skills. The stronger readers get more challenging books, and the struggling readers get a book on their level. There is a huge business in putting out sets of leveled books and assessments to determine each student’s reading level. And the result? In general, research has found that leveled reading reduces the achievement of the readers who struggle the most. We might intuitively think that reading an easier book would benefit students who have weaker reading skills, but that intuition seems to be wrong.

Ok but all of those try to take a class of students and meet students where they are. What about assigning students to classes based on their achievement? In the US this is typically called tracking or ability grouping. It’s a complex and controversial topic. The research base is hard to read because there are a lot of ideologically motivated researchers who are either for or against tracking and want to see the evidence a certain way. But the biggest theme in the research is that the effects are small. There are plenty of meta-analyses that find an effect near zero (here’s one example). You can slice and dice these results lots of ways. Schooling is complex and there are lots of different ways to implement tracking. Maybe there are some gains to be found. But the theme so far is that tracking isn’t coming to save us.

Psychological research consistently shows that humans are conformist creatures. We instinctively align our behaviors to group norms. Classic studies like Asch’s line experiments, where 75% of participants denied obvious truths to match group answers, remind us that humans are social and prioritize conformity. This tendency isn’t just peer pressure, it’s evolutionary wiring. For our ancestors, conforming boosted survival by maintaining group harmony and reducing conflict. Today, this manifests in classrooms where low-structure learners thrive on collective routines. Conformity explains why personalized learning often fails. Most students need the social scaffolding of lockstep instruction, even when it’s inefficient. Conformity isn’t a perfect solution, but it’s the best one we have.

One form of learning that has been shown to be particularly effective is deliberate practice. Deliberate practice involves being pushed outside of your comfort zone, focusing on specific, concrete goals to improve performance, and getting consistent feedback. One common characteristic of deliberate practice is that it isn’t particularly fun. Most contexts where deliberate practice is common, like sports and music training, involve expert, individualized coaching. The coach is mostly there for motivation. The coach does other things as well, but the most important thing a coach can do is motivate you to train. Deliberate practice isn’t common in school learning, but it’s a good reminder that motivation is the key to lots of forms of learning in and out of school. Learning isn’t always going to be a ton of fun. In the absence of one-on-one tutoring for every student, conformity is the best tool we have to create the motivation necessary for learning.

These two failures—self-paced technology and ability grouping—get at a deeper truth. Working at your own pace may seem like it makes sense, but it often undermines motivation. Grouping students by ability, whether within or across classrooms, has shown little benefit. Neither approach has delivered the transformation its advocates promised.

But Personalization Works for Some Kids?

Let’s explore personalization a bit more. Clearly this personalized learning thing works for some students. Maybe 5%. Maybe 10%. Why?

Here’s a broad generalization about learning. Let’s take the basics of learning to read as an example, where there is a wealth of data to back up the generalization. Some students will learn to read no matter what they experience in school. Often their parents teach them, or an older sibling or neighbor, and they pick it up quickly. Others more or less teach themselves. This group doesn’t benefit much from organized school, at least in terms of learning to read. We might call these “no-structure learners.” A second group needs the structure of school, but the quality of the teaching doesn’t matter too much. As long as they get the basics, a solid exposure to reading, and some support from a teacher, they will learn to read just fine. We might call these “low-structure learners.” Then there’s a third group. This group will struggle to learn to read. For this group, the quality of teaching matters enormously. Some will be diagnosed with dyslexia, though a strong course of synthetic phonics will reduce that number. Many will learn the basics but still struggle with things like multi-syllable words for years to come if they aren’t taught well. A carefully-sequenced, well-taught curriculum can make a large difference for these students. We might call these “high-structure learners.” There aren’t sharp divisions between these three groups, and motivation depends on context, so students may have a different motivation profile for a different subject or something outside of school. This is the answer to why personalization only works for 5% of students. Students need different levels of structure in order to succeed.

For another example, we see the same phenomenon with math facts like times tables. Some students seem to learn them by osmosis, or they pick them up entirely outside of school. Many more need a bit of structured practice, but learn their facts without much trouble and move on. Some struggle with multiplication facts for years. The structure provided isn’t enough, the curriculum moves on, and these students often struggle in math for years to come. For one example of a high-structure teaching strategy, incremental rehearsal is a highly-structured way to teach students multiplication facts.

This phenomenon is well-studied with phonics and math facts, but you could apply it to any other domain. Imagine a college computer science department. The no-structure learner is that student who is always coding on their own, learning stuff from Stack Overflow, and only occasionally going to class to make sure they get their degree. The low-structure learner shows up to class. They aren’t learning too much on their own, and coursework is motivation enough to learn and get a solid foundation in computer science. The high-structure learner has a hard time. They’re the student showing up to office hours all the time, using the tutoring center, using all the support they can find. Maybe they push through, maybe they can’t cut it and switch to a major in communications.

The same phenomenon shows up in pandemic learning loss. Learning loss was concentrated mostly in the lowest-achieving students. Many high-achieving students did fine; these are students who didn’t need the structure of school, or for whom the minimal structure of online coursework was enough to keep them moving forward. The high-structure students who already struggle in school lost the most ground.

Low- and no-structure learners help us understand a broader phenomenon: for many students, school quality doesn’t seem to matter very much. One illustration is that in randomized controlled trials, school assignment doesn’t seem to play a very large role in academic achievement. Freddie deBoer collected this research in his essay Education Doesn’t Work. I’ll quote him here:

Winning a lottery to attend a supposedly better school in Chicago makes no difference for educational outcomes. In New York? Makes no difference. What determines college completion rates, high school quality? No, that makes no difference; what matters is “pre-entry ability.” How about private vs. public schools? Corrected for underlying demographic differences, it makes no difference. (Private school voucher programs have tended to yield disastrous research results.) Parents in many cities are obsessive about getting their kids into competitive exam high schools, but when you adjust for differences in ability, attending them makes no difference.

We could pick apart these studies and I’m sure we could find examples where there is a difference, but that difference will be small.

Here are two quick anecdotes from my personal experience. I often have bright students whose parents request they get some more advanced work. I try to lay out for them a few options for more challenging work I can provide students, but I’m also clear that I am one human and I can’t teach the student for significant chunks of time each day. I can provide some resources, I can check in with them and answer their questions, but the student needs to be motivated to engage with some challenges. In the vast majority of cases, the student never touches the challenge work. Their parents bug them about it, I bug them about it, but they just can’t summon the motivation. These students are willing to keep up with our regular coursework, chugging along with content they mostly already know or can learn in a fraction of the time that it takes many of their peers. But working on their own is beyond them. To be clear, this isn’t every student. But it’s a large majority, another illustration of the 5 percent problem.

Second, online charter schools have spread rapidly in the last ten years. In my state it’s not very hard for students to enroll. I’ve had a number of students unenroll from our local public school and start at an online charter school. Most are back within a few months. They generally say one or both of two things: first, that they are bored learning on their own and they miss having people around. And second, they just weren’t motivated and didn’t learn much. Now to be clear, I’m in favor of having some online charter schools. They are a great option for some students – students who can summon the motivation, students with outside-of-school circumstances that make attending school challenging. It’s the 5 percent problem. There’s a 5 percent, those no-structure learners or students in other unique situations, who benefit from options like online charter schools. But the vast majority do best in the age-graded schools we already have.

You might think that we’ve found the solution to tracking. We just need to get all the no- and low-structure learners together and let them move much faster. Here’s the issue. The no-structure learners will always be bored, as long as we are committed to putting them into classrooms where everyone learns the same thing. And those classrooms where everyone learns the same thing are exactly what the low-structure learners need. As soon as you create a higher track there will be a ton of demand for it. Parents will insist that their kid join. And as it grows, it won’t be able to accelerate very quickly. You still need the structure of a classroom where everyone is learning the same thing, and that just isn’t a very efficient way to teach.

A good illustration of this point is to visit a gifted or exam school. If a few of those 100 classrooms from our observation thought experiment were gifted schools or schools with an entrance exam, you might be surprised by what you see. They would be doing more advanced work than peers in regular schools, absolutely. But often only by a year or two. You’d see all the same inefficiencies of students all learning the same thing at the same pace. You’d see lots of bored students who could be going faster. You’d see a bunch of students who you’re surprised are in this school at all. It’s the reality of the system we have.

No-structure learners thrive anywhere. Low-structure learners need any coherent system. High-structure learners are much more sensitive to the quality of teaching, but trying to meet each student where they are doesn’t work very well. Lumping everyone together and asking them all to learn the same curriculum seems to work better at scale than anything else we’ve tried. These are the core challenges of education.

What’s Happening Under the Hood?

If we know there are no-, low-, and high-structure learners, then the key question becomes: what internal levers predict who ends up where?

I see three main factors. First is intrinsic motivation. This isn’t a review of self-determination theory, but the short version is that some students have a lot of intrinsic motivation, others have less, and some have little at all. Second is the set of habits students bring to school. When you observe students in school, one thing that’s often striking is how some students are in the habit of completing assignments, reading when they’re asked to read, solving math problems on a worksheet when asked, and so on. Others don’t have those habits. You’ve got no-structure learners, who would happily do that learning on their own. Low-structure learners, for whom the basic structure of school and class is enough to keep positive habits going. And then high-structure learners, who are in the habit of avoiding schoolwork whenever they can. Finally, there’s fluid intelligence. Students with a high processing speed and high working memory capacity are better at learning without much structure. They have the mental tools to connect the dots and figure things out with less structure. Students without those cognitive capacities need additional structure in order to learn.

Those elements are self-reinforcing. Motivation tends to beget motivation. Habits become stronger over time. Students with less fluid intelligence learn less in school, which exacerbates the consequences of less fluid intelligence. This doesn’t mean that a kid can’t change their trajectory. It’s possible to change habits, and to develop new sources of motivation. A broad base of knowledge helps to mitigate a lack of fluid intelligence. Motivation and habits are context-specific, so students might have a different profile in a different subject. But on average, students tend to stay about where they are in the no-structure, low-structure, and high-structure spectrum.

Students don’t always neatly fall into one category or another. They can shift over time, or be very intrinsically motivated yet have other challenges that require a lot of structure. Students can have different profiles in different subjects. Still, this broad taxonomy is a useful way to understand why tactics like personalization work for some students and not others, and why the basic structure of school has lasted so long.

The Thesis, Again

One way to interpret the design of school is that it’s trying to provide just enough structure to get students to learn the basics of the school curriculum. Putting kids in front of a computer on their own isn’t going to do the trick.

Schools are given a huge challenge. The goal isn’t to educate the students who are easiest to teach, or most eager to learn. The goal is to educate everyone. The core challenge of compulsory public education is motivation. The best solution we’ve found is to send kids to school beginning at age 5 (or earlier if we can), before they can reliably form long-term episodic memories. Talk to a typical high school student, and they have literally been going to school as long as they can remember. We group students by age in part because it’s the easiest way to organize the system. The system motivates high-structure learners to keep up with their peers, though that motivation does gradually fade over time. Grouping by age also provides just enough structure for low-structure learners to stay on track – not that it’s particularly efficient, but it can help schools be reasonably confident that those low-structure learners will get a broad foundation in the school curriculum. In the same way that democracy is the worst form of government ever invented except for all the others, conventional school is the worst form of motivating students to learn except for all the others. All that leads to the obvious, inevitable problems. Some students are ready to move faster, some students need more support. Schools and teachers often try to help, and occasionally experiment in bold ways, but there’s this enormous gravity that pulls back toward the conventions of a typical school. It’s easy to point out these obvious challenges and claim that school is broken, that we should blow up the system and invent something better. It’s much harder to ask why the fence is there, and understand it before taking it down.

Here’s something you have to remember. It’s easy to cherry-pick in education. If you want to start a school to prove that penguin-based learning is the future, that penguin meditation and penguin-themed classrooms are superior to the stuffy, traditional, obsolete schools we have now, you can. It’s simple. Find a way to only accept no-structure and very low-structure learners. Then start your school. Do your penguin meditation, make sure there’s a basic structure for learning core academic skills, and you’re set. The results will be great, you can publish articles about the success of your method, if you’re lucky you’ll get some of that sweet sweet philanthropy money.

Cherry-picking isn’t always that blatant. If you just manage to get a few more low-structure learners and fewer high-structure learners in your school it will make a difference. Your test scores will look better than the school down the street. Schools spend a huge fraction of their resources on special education, providing the structure and systems that those students need. Just having fewer students who need that level of resources will free up time and energy to focus on everyone else, and the selection effects will make it look like you’re doing a good job. The difference doesn’t have to be huge to help the school do a little better.

What if we were brutally honest when a family enrolls their child in school? Here’s what we would say:

If your child is a no-structure learner, they will be bored here. They will probably learn some things, but they will often sit in lessons where they know everything the teacher is teaching, and they’ll spend a lot of their time sitting around waiting for other students to catch up. If your child is a low-structure learner, they will still often be bored as our school isn’t very efficient, but the structure and routine will ensure they get a basic level of literacy and numeracy. Maybe they’ll like school, probably because of gym class and being around their friends, maybe they won’t, but they’ll learn some things. That said, the school you pick doesn’t matter too much. Your child will learn about as much anywhere else. If your child is a high-structure learner, they will need a lot of very structured teaching. Our teachers vary widely: some are good at providing that structure, others aren’t. Your child will gradually fall behind, and will perpetually feel a bit dumb and a bit slow compared to everyone else. But we will do our best to keep them moving along with their peers because that’s the best idea we have to motivate them. Hopefully, with some help, they’ll graduate high school on time. There’s a risk they just won’t have the skills, or they’ll be discouraged by constantly feeling dumb and just give up. Oh, and we aren’t very good at understanding what causes students to be motivated. It’s absolutely correlated with socioeconomic status, so it would be helpful if you’re rich, but there’s a lot of variability and plenty of rich kids need that structure too.

Some History

It’s worth taking a quick detour through the history of education in the US. When did age-graded schools become common? The story is a bit different than many common conceptions of how education has worked in the US. White people in the US, particularly men, had a relatively high literacy rate by 1800, higher than most other countries at the time except perhaps Scotland. But the education system was fragmented. It was a mix of religious education, local cooperatives, apprenticeships, formal schooling for the rich, and public education for the poor in cities. The common school movement emerged between 1830 and 1860. The goal of the movement wasn’t to increase the average education of the populace, and it didn’t cause any large increase in the literacy rate. Instead, the primary rationale was the importance of a common education system for democracy. Democracy felt fragile in the first half of the 19th century, and universal public education was the solution.

The explicit goals of the common schools movement were to instill in students the importance of citizenship and morality. Age-graded schools were a natural next step: students should travel through school in a cohort of their peers, learning together the basics of reading, writing, and arithmetic, and the importance of education for the country’s young democracy. While these schools certainly did teach reading, writing, and arithmetic, the curriculum of the school played a secondary role to its common character. The most important goal of school reformers was to move education into common schools; whether learning happened in those schools was a secondary goal. It’s interesting that maximizing learning was never the goal of universal education.

The common school movement focused on what we would now call elementary and middle schools. It wasn’t until the 20th century that attendance in high school became widespread and then compulsory. And high school is the place where this giant compromise starts to fall apart. Even when the high school became widespread, there was broad disagreement about what high school should teach. Should high schools retain the liberal arts focus that they had when only the rich had access? Should they focus on the trades and career education? Should high schools offer a core course of study to all students, or use tracking to separate students who are college-bound from those who are not? These are the perennial questions that high schools wrestle with, and they are a logical outgrowth of the core tension of using age-graded schools. The goal still wasn’t about learning; it was about what the credentials were and who had access to those credentials. Only in the last few decades have schools tried to focus on maximizing learning. According to NAEP data there was some increase in scores between the late 80s or 90s depending on the subject and about 2012, after which there was stagnation or a slow decline, accelerated by the pandemic learning loss. This is a conjecture without any real evidence, but the increase in education technology and personalized learning software coincides with that stagnation in national test scores. The rise in test scores didn’t involve any large changes in the basic structure of school, it was driven by a lot of legislation and rhetoric around “no child left behind” and trying to support students who previously fell through the cracks.

School is Conservative

One common frustration for those who believe that schools can do better is how conservative the education system is. While there are pockets of innovation and experimentation, most schools are bureaucratic and slow to change. This is often viewed as a failure: why are our schools so obsolete and slow to adapt to the needs of the 21st century?

What if the education system is conservative for good reasons? We have always looked to education as the solution to our social problems. In the 19th century, education existed to buttress our democracy. In the first half of the 20th century, education was asked to promote social mobility. In the second half of the 20th century, education was asked to contribute to our national defense.

Maybe the best way education can contribute to all of these causes is to focus on providing a broad, basic education to as many children as possible, and maybe our current system is the best idea we’ve had so far for doing so. If education chased every fad that came along, it might be in much worse shape. It was only a few years ago that a lot of people were arguing that we should teach more kids to code. Now it looks like coding might be one of the first jobs AI can do for us. For the last few decades, many thought leaders have advocated that we reorient our education system away from antiquated content that kids can look up on Google, and instead teach critical thinking. There’s ample evidence that we can’t actually teach critical thinking divorced from content. And education seems to increase IQ, so maybe we’re already teaching critical thinking by giving students a broad, basic education.

The reality is that elementary and middle schools haven’t changed much over time. High schools, however, are the place where the drive to motivate students breaks down. At that point, low-structure and high-structure students are pretty far apart from one another. High schools handle this in a variety of ways. Some high schools specialize, either as test-in schools or schools with a particular theme. Private high schools play a role supporting high-achieving students. And at comprehensive public high schools, there is more tracking and separate experiences for students. An increasing number of high schools offer community college courses through dual enrollment, as well as a wide variety of electives. Other students move into a vocational track, with some remediation in core literacy and numeracy skills and coursework designed for careers rather than college.

This is logical if we look at school as a system designed to maximize motivation: by the time students reach high school, the gaps in academic knowledge have widened to a point where it isn’t practical to keep students in the same classroom. Most elementary and middle schools promote students socially, at least if they put some effort in. But in high school, students need to amass credits and/or pass exams to graduate, and keeping everyone in the same classroom learning the same content won’t get some students the credits they need. We see what you would expect: motivation plummets. Remember those 100 classrooms you imagined visiting? Some of them would be lower-level high school classes. Those are often sad classrooms to spend time in. Students aren’t doing very much, expectations are clearly low, there isn’t much learning happening. Schools often explicitly create easier avenues to graduate for some students, through credit recovery programs or similar ways to give credit to students who aren’t putting in much effort. It’s logical that motivation plummets: students are no longer motivated by staying with their grade-level peers.

Practicalities

What good is the hypothesis that school is designed to maximize motivation? It can help us understand all sorts of phenomena. I often hear an argument from homeschoolers that they can accomplish in two hours a day (or some other small amount of time) what schools do in seven or eight. I don’t doubt that at all. Schools aren’t particularly efficient at facilitating learning. Schools are good at educating everyone at once.

We can also better understand learning loss from the pandemic. Learning in school isn’t particularly efficient, so one might assume that missing a few months of school won’t have a big impact. But habits are powerful. What changed was motivation. During the pandemic, many students lost their long-held habits of attending and putting in effort at school. Interestingly, learning loss happened both in states that had extended school closure and those that returned to full-time school more quickly. In both cases, students lost those habits, and the power of conformity started working against school motivation, rather than in favor of it.

We can understand why school sports are such a powerful and enduring phenomenon: motivation is the core challenge of school, and conformity is our best solution. Team sports are a great mechanism to motivate young people, so we attach sports to school to capture a bit of that motivation.

We can understand why, despite lots of hype, AI hasn’t revolutionized education. Most AI applications pay little attention to motivation, and try to personalize learning in exactly the ways personalized learning has failed. AI may yet transform education, in any number of ways. But in the short term, AI has been naive about motivation in exactly the same way as all the other education transformations that have fallen short.

We can understand why there have been so many attempts to revolutionize schools, but they have struggled whenever they try to scale. If you have the right group of students, lots of things might seem to work. When you try to scale them to meet the true needs of universal education, they will run into the same roadblocks education has always struggled with. Then, the education system will be blamed for being obsolete, and we will continue to invent new approaches to education that ignore the same basic challenges of motivation.

Something I haven’t addressed is the harsh reality of school for many kids. Everyone’s experience is different, but there are countless stories of students getting bullied, verbally abused by teachers, deprived of bodily autonomy and freedom of movement. This can all be true. I don’t want to hide from these realities; I’m a teacher, I’ve seen them. Walk into a typical middle school and you will quickly learn the byzantine collection of rules about going to the bathroom. It’s not something I’m proud of, and I’m not arguing that it’s a good thing. But policing the bathrooms, and many related minutiae of students’ lives, is a byproduct of the reality of school. We require all students to attend compulsory education of some kind. Some schools are able to filter out more of the high-structure learners. In those schools you won’t find nearly as many rules about using the bathroom, and you will also find far less bathroom vandalism. In the schools that are left to educate everyone else, we are left with the reality of trying to motivate students as best we can. We struggle with the students who predictably lash out because they are bored with moving too slow, or constantly confused as the curriculum moves too fast. We double down on conformity and structure, not because they are perfect solutions but because they’re coping strategies to deal with some of the ugly realities of mass compulsory education.

This isn’t to say schools respond appropriately in every situation. There are tens of thousands of schools, each left to their own devices to figure out the best way to educate their charges. Humans make mistakes, and when we scale a profession to the size of our public education system we have to do the best with the teachers and school leaders we have. I’ve been party to plenty of school policies I disagree with. I’m not trying to defend them, just to help readers understand where they come from.

A Prediction

I’ve used the word “designed” loosely in this essay. Age-graded classrooms are schools’ most valuable asset, but they weren’t deliberately designed. They came about by an accident of history, and they have stuck around because we haven’t figured out anything better. That lack of self-awareness will always be education’s Achilles heel.

Where will we go from here? I hope I’ve been clear that I don’t think schools are perfect. They are designed to maximize motivation, but motivation is hard to maximize, and schools don’t do a great job. Is there a better way? Maybe. But to design a better education system, we first need to understand what the current system does well. Don’t tear down the fence until you understand why it’s there. The basic structure of age-graded schools that teach the same content to students of a given age has a purpose. You might have your own ideas about what schools should do and how they should do it. You might have some good ideas. But attacking schools without understanding the basics of how they function will never change anything.

One central contradiction of schools is that schools themselves don’t understand the purpose of age-graded schooling very well. There’s constant rhetoric from teachers and school leaders about the need to meet students where they are, to move past our antiquated one-size-fits-all education system and innovate. The purpose of this essay is to review school: to understand how it works, and where its structure comes from. This review leads me to a prediction: the structure of schooling won’t change. People will continue to try to disrupt the status quo. There will be plenty of tinkering around the edges. Some of that tinkering will catch on at a broader scale. But there will be an inevitable gravity back to the status quo. That gravity exists because the status quo is the best tool we have to educate a huge number of students. It’s not particularly good at fostering learning, but at scale it’s better than anything else we’ve tried. The push and pull will continue, the criticisms of school will continue, the experimenting will continue, but the basic structure will never change.

.png)